After my recent podcast episode contrasting Prescriptive Instruction vs Self-Organization approaches to skill acquisition I have received a lot of great questions and comments regarding how specific training activities fit with the different approaches. So, to further explore the relationship between them I am going to try and do a few blog posts where I directly compare different methods for training the same sports skill. The purpose of these is not to make claims about which is better (although, I obviously have an opinion!) but rather to help clarify (the often subtle) differences between the two. My goal is really to illustrate the concepts and to show the same tools and similar activities can be used differently for each approach. I have deliberately chosen examples of what I think are excellent practice design – that is, activities that have a clear rationale and purpose.

The Issue: Baseball Pitching & “Forearm Flyout”

The sports skill I want to focus on for this comparison is baseball pitching and the issue is a technical problem called “forearm flyout”. During a pitching delivery its very important that a pitcher’s arm not get too far separated from their body for two reasons. First, it can lead to decreased velocity in the outcome of the pitch because the pitcher will not optimally achieve Bernstein’s stage 3 in his skill model – the exploitation of external forces. In particular, if the arm separates from the body too early in the delivery, the pitcher is breaking the kinetic chain. That is, instead of letting the forces travel smoothly and systematically from the ground, to the big muscles in the legs, to the torso, to big muscles in arm, to the hand, they are putting all the force in the peripheral degrees of freedom (the elbow and forearm) too early.

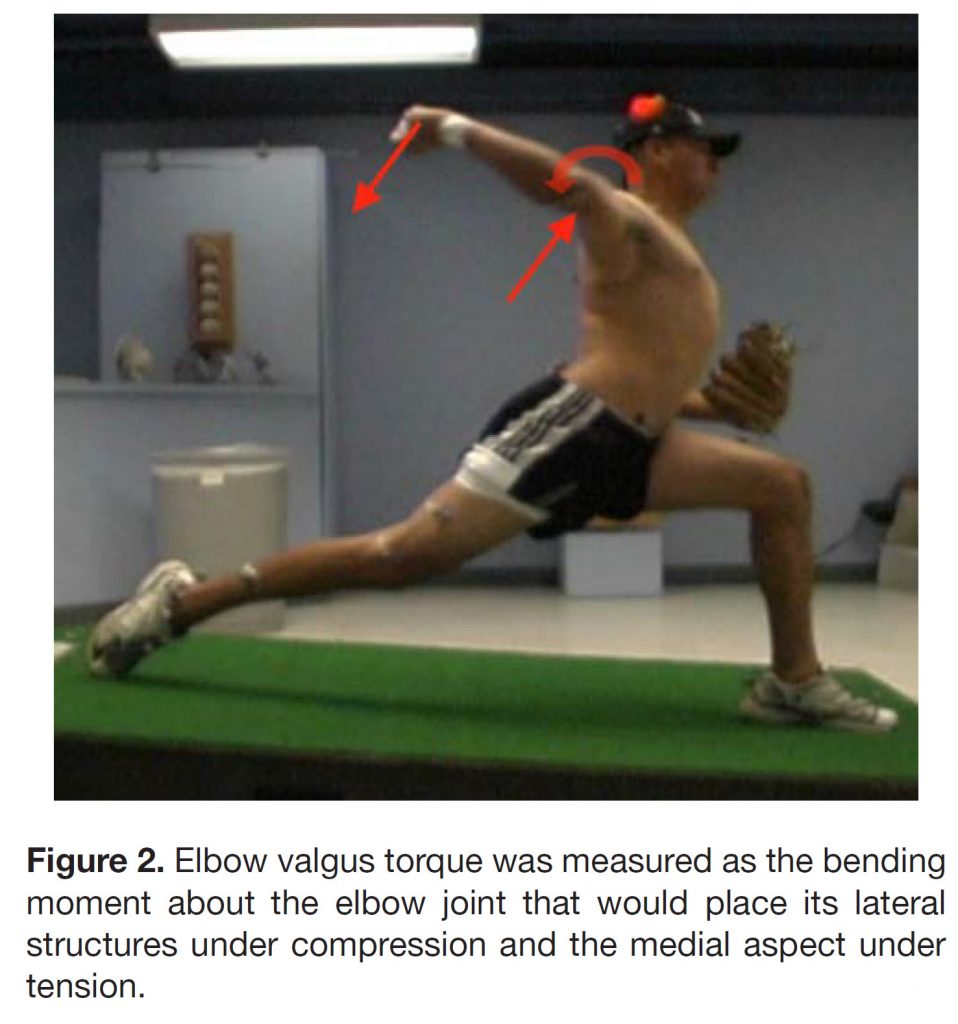

A second more serious issue is the potential for pain and injury. In particular tearing the Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL) in elbow. In their study, Aguinaldo and Chambers (2009) provided a biomechanical description of this issue. Specifically, “forearm flyout” is when the angle between the pitcher’s forearm and humerus (upper arm) exceeds 90 deg. They measured the amount of vagus torque (i.e. outwards rotational force away from the body midline) at the elbow during pitching and related it to several kinematic variables. One of the main findings was that “elbow flexion appeared to be associated with reduced elbow valgus torque”. In other words, having more bend around the elbow (smaller value of the angle shown in the figure below) leads to less torque and less chance of injury. The authors concluded that “these biomechanical findings offer additional scientific feedback for developing methods used to minimize the effects of valgus loading on these injuries”. And that’s exactly what we are going to try and do!

The Traditional, Prescriptive Instruction Approach

Goal: To try and correct the technical flaw of “forearm flyout” and get the pitcher to throw with an ideal technique.

Assumption #1: There is an ideal technique (body positioning) for pitching with possibly some small bandwidth around it.

Assumption #2: The performer can explicitly/consciously make technical adjustments.

Practice Methods: Cueing, Manipulations of task conditions to get pitcher to “feel” the correct technique, Corrective Feedback

In the traditional approach, there are a lot of different ways that we could try to tackle this issue. This could range from the use of internal, bodily focused cues (“try to always keep a bend in your arm”) to the use of an external focus of attention cue (“keep your wristband always pointing in towards the mound”) to the use of analogies (“imagine that you are squeezing a beach ball between your upper and lower arm while throwing”). We might also consider changing the conditions in practice by altering the task in some way. This is shown nicely in the video below with a connection ball practice activity used by the coaches at Baseball Rebellion. Note that, although they are not talking specifically about the issue of “forearm flyout”, I think it illustrates the point:

Clearly, in this activity, the goal is to get the pitcher to adopt a particular technique – not only their elbow angle but also with regards to the alignment/timing of the movement of other body parts. The big yellow Connection Ball is used here primarily with the purpose of getting the pitcher to “feel” what the correct technique is like. Although not shown in that video, typically this would be accompanied by some cues and corrective feedback (e.g., if the pitcher opened up the forearm angle too early and dropped the connection ball the coach would come with feedback and a cue about body posture). I call the Connection Ball a condition of practice (not a constraint!) here because its purpose is prescriptive.

Here is another example of using the Connection Ball in a prescriptive manner:

Another element of this type of approach we might often see is a discussion/reflection between the coach and athlete talking about what the correct technique is and how to implement it.

The Self-Organization Approach

Goal: To try and de-stabilize the existing movement solution and encourage the pitcher to explore other options.

Assumption #1: The coach does not know the ideal technique the pitcher should be using (i.e. the angle the arm SHOULD be bent at and how to exactly position the body during delivery) — they have only identified a non-optimal solution that likely will result in injury.

Assumption #2: The pitcher cannot consciously/explicitly solve the problem by deliberately changing specific aspects of the movement in response to specific cues from the coach and their own reflection. The movement is occurring too quickly and the problem of coordination in is too complex. Or as Frans Bosch would say: “The body has very little interest in what the coach has to say.”

Practice Methods: Differential Learning (DL), The Constraints-Led Approach (CLA)

In the self-organization approach, there are also many different ways we could design practice activities to encourage the pitcher to find a new movement solution. If we used DL, we would have the pitcher make several different pitches each with a different body posture (e.g. hands starting low, hands high, narrow leg stance, wide leg stance). So, in a sense, we would be telling the pitcher how to throw on each attempt (i.e. what body posture to adopt) but for a completely different reason. Instead of trying to move towards an ideal we are forcing them to try a very large number of movements (most of which they would not use in the end) and explore a larger area of task space.

But the method I want to focus on here is the CLA, in particular using the same Connection Ball tool that was used in the traditional approach videos above. When using the Connection Ball in a CLA approach, the pitcher is given a new goal for the practice activity: move so that, when you pitch, the connection ball goes towards plate when it flies out. No other instruction about how to achieve this or feedback is given. Here is a vide demo from Driveline:

The main purpose of the Connection Ball here is to destabilize the current, undesired movement solution. If you look at the 3rd throw this pitcher makes you can see that when his forearm separates too early, the ball falls out early in the delivery and goes sideways. In other words, you can’t achieve the goal of the task (make the connection ball go forward) with your current technique. This makes it unstable and encourages you to find another solution. But, critically, the particulars of this new solution are completely up to the individual. The pitcher is given no instruction about how to change their delivery or feedback about the “correctness” of these changes. For this reason, here I call the Connection Ball a Constraint – it is being used to prevent the pitcher from using their old, dangerous movement solution (i.e. it is constraining them, thus the name) but with the goal being Self-Organization.

In the Self-Organization approach, discussion and reflection specific to mechanics and technique will be of little value because it is not believed that movement problems are solved explicitly. To expand on Frans’ saying, in terms of coordination: “The body has very little interest in what the coach has to say OR what the athlete thinks”. But that is not to say that discussion/reflection can’t have value – they are very important for clarifying intentions, motivation, etc.

Key Differences

In summary, here are a few key differences I see between these approaches:

Condition vs Constraint – Altering the conditions of practice is for the purpose of the prescription of an ideal technique. Manipulating constraints is for the purpose of de-stabilizing the existing movement solution and encouraging exploration to a new one. If the solution space is a field, conditions are a fence that goes all around you and makes you stay in one part of the field. Constraints are a barrier that blocks you from going to one area but encourages you to go anywhere else!

Goal of the practice activity – In the traditional approach, the goal of the practice is technique. It is to get the athlete to move in a certain way. In the CLA approach, performers are typically given a simple outcome-oriented goal (make the connection ball go forward) in the practice task. In the Self-Organization approach, it is believed that the coordination solution can only be understood in context of the task (and individual and environmental) constraints.

Source of feedback – In most prescriptive practice activities, the performer must rely on feedback from the coach to know if they are moving towards the correct technique. In a well designed CLA drill, the feedback will be intrinsic (something the athlete can detect on their own) like the connection ball moving in the wrong direction.

What to do if the activity is not working – In the traditional approach, if the athlete is not adopting the desired technique the first recourse would typically, of course, be some type of corrective verbal feedback (“Try starting to bend you elbow when..”) Then one might try using a different cue.

In the self-organization approach, if the performer is not solving the movement problem successfully a coach might try adding differential learning on top of the CLA. For example, something like: “this time you throw the connection ball start with your feet close together”. This could push the performer to try a solution they hadn’t before. But, critically, the instruction given here is not corrective – in fact, the opposite is true – the more random and unusual it is, likely the better!

A final thing I will emphasize is a point I have been trying to make a lot lately: it is OK for your practice activity to be unrepresentative if it is for a purpose. Obviously, a baseball pitcher doesn’t ever throw with a big yellow ball under their arm during a game so all the activities I have described are non-representative in that regard. However, whether for the purpose of feeling the correct technique or adding a constraint, I think the connection ball is a useful, purposeful break from representativeness. You don’t always have to be “as close to game like as possible” in every aspect of training as long as you have a rationale for moving in the other direction!