Following up on my new paper that just came out today, showing the skill acquisition/performance benefits of deliberating practicing undesired outcomes, I wanted to share some data I collected that I did not include in the paper.

For those that have not read it, in Experiment 2 of this study I compared baseball batting performance pre and post-training for two training groups: One that always practiced producing the desired outcome (i.e., hitting the ball hard into fair play) and one that practiced only undesired performance outcomes (i.e., “Right Way” training), with a different outcome for each training session: hit a pop fly, hit the ball into the ground, hit a foul ball to the left, hit a foul ball to the right, and hit a ball at the shortstop (“Wrong Way” training). Both groups were given no technical instructions or corrective feedback (i.e., they were not told how to produce their intended outcome). They trained in a virtual environment for 6 weeks. See experiment 1 for a comparison with a more traditionally coached group and a control group.

In both experiments, the “wrong way” group had a significantly larger increase in hits, adapted more effectively to variations in pitch trajectory, and demonstrated superior affordance perception (e.g., not swinging at pitches out of the strike zone and ones that would have likely led to hitting into the defense) as compared to the “right way” and the control group. As I say in the paper:

” The effects found here challenge the traditional conceptualization of skill acquisition in sports, where it is proposed that the goal of practice is to develop memory structures (e.g., a motor program, muscle memory) for producing the desired outcome through repetition. Instead, the present findings are more consistent with the Ecological Dynamics’ conceptualization of motor skill acquisition as an adaptive, problem-solving process wherein the performer is learning to find different movement solutions (i.e., move to different areas of the solution space) to achieve their goal under different constraints. Stated another way, being skillful is not a process of repeating a solution, it is repeating the process of finding a solution”

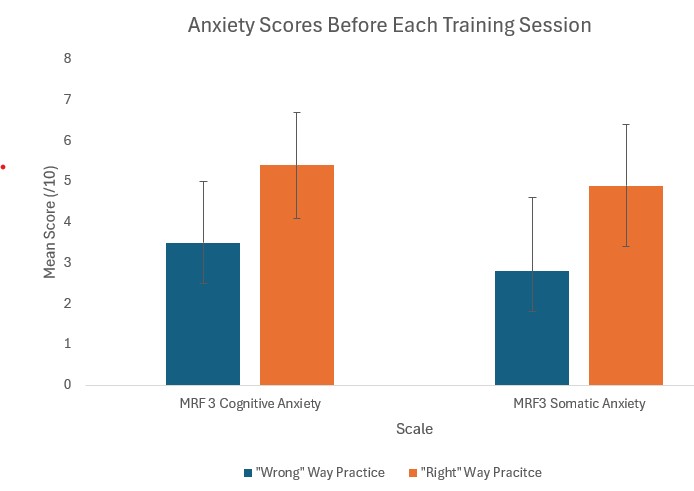

In piloting this study, several participants commented that practicing the “wrong way” seemed to take the pressure off…failing to produce an undesired outcome did not seem to be such a big deal! It seemed more like “playing” or “messing around” than normal practice. To test this idea, I used the Mental Readiness Form-3 (MRF-3; Krane, 1994). The MRF-3 has three bipolar 11-point likert scales that are anchored at the extremes with not worried and worried for cognitive anxiety; and not tense and tense for somatic anxiety. This measure is a shorter alternative to the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2; Martens, Burton, Vealey, Bump, & Smith, 1990) that I have used in previous research a few times. Batters completed these scales before each practice session. The mean results are shown below.

Consistent with the informal observations, both cognitive and somatic anxiety were significantly lower for the group that practiced producing undesired performance outcomes.

References:

Gray, Rob, (2025). The Value of Practicing the “Wrong” Way: Skill Development and Affordance Perception Through Broad Exploration of the Solution Space. Journal of Motor Learning and Development.

Krane, V. (1994). The mental readiness form as a measure of competitive state anxiety. The Sport Psychologist, 8, 189–202.

Martens, R., Burton, D., Vealey, R. S., Bump, L. A., & Smith, D. E. (1990). Development and validation of the competitive state anxiety inventory-2 (CSAI-2). In R. Martens, R. S. Vealey, & D. Burton (Eds.), Competitive Anxiety in Sport (pp. 117–173). Champaign: Human Kinetics.